We’re back in the 1950s. The Opel Kadett and Kapitän are still rolling down Germany’s roads; shop windows are stocked with petticoats and hats, and buffets serve up deviled eggs and meatloaf. On the weekends, racing fever runs rampant in the country. However, there’s no loud roar of the engines to be heard here: These vehicles rely on gravity alone to move. Soap box derbies have a magical attraction for participants and spectators alike. By 1953, competitions were being held in 200 cities, and more than 10,000 children and teens built their own racers and rattled their way to the starting ramps.

80,000 PEOPLE AT THE ALL-AMERICAN SOAP BOX DERBY

The sport came to Europe from the United States. Races were scheduled as early as 1949; the German Youth Activities (GYA) program, which was operated by the American forces occupying Germany, sponsored the series of races. In America, soap box derbies had already been a big attraction for some time. In Akron, Ohio, for instance, more than 80,000 spectators would regularly gather to see which child would win the world championship title in the All-American Soap Box Derby. The first races in the USA were staged in 1933 in Dayton, Ohio. The idea came from a soap manufacturer who had the outline of a child’s car printed on the large wooden crates that held his product. The structure of the car could be easily carved out with a saw and a wood plane, and the soap maker cleverly included axles, wheels, control cables, and a steering wheel in the boxes. The little vehicles got their name from these materials: soap box racers.

CHILDREN BUILT WOODEN CARS AS EARLY AS 1904

In Germany, Opel got involved in this new sport shortly after the end of World War II. And with good reason: The speedy wooden boxes were very much going back to their roots. In 1904, Germany was in the grips of automobile fever, and children began building the first small wooden cars. These children were inspired by the legendary Gordon Bennett Cup, which had its starting point in Germany for the first time ever that year: On 17 June, the race began in the city of Oberursel in the Taunus mountains, and it drew the elites from the racing world to Hesse. Though trendy at the time, it proved to have long-lasting appeal.

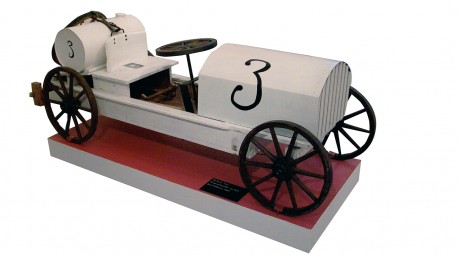

White box: That vehicle is exhibited in the Vortaunus Museum in Oberursel. It is the miniaturized replica of Carl Jörns’ Opel race car from 1907.

RACE CAR RIVALS ON THE TAUNUS SLOPES

Most of the children watching the race wanted nothing more than to become race car drivers themselves. Their desire to emulate their heroes was what helped them achieve their goal. They constructed their own miniature race cars that could be pushed, foot-powered, or simply rolled down an incline. On 31 July 1904, during the summer festival of Humor, a local civic association, these racing rivals met for the first time on the slopes of the Taunus mountains: 16 hand-crafted wooden cars rolled up to the starting line.

1907 IMPERIAL CUP RACE: JÖRNS HITS THE GAS WITH OPEL

Nearly three years to the day after that race, the wooden miniatures began to take on shape and form. At the “Kaiserpreis-Rennen” (Imperial Cup Race) in Usingen, Carl Jörns placed third in his Opel and received the award for the best German car. The next generation of engine-less racers now had a role model whose success they wanted to emulate. Jörns’ Opel became the model for 40 wooden cars whose chassis came from baby buggies, hay carts, luggage trolleys, or small carriages. On 21 July 1907, the little cars rolled down the hills in Usingen – the overwhelming response from the spectators and the excitement of the participants (and their fathers) quickly led to further races with these wooden cars.

FALSE PRIDE AND CRIMINAL INTENT

So Oberursel is the birthplace of the soap box racer – or at least one of its forebears, right? No one is exactly sure. Stories tell of a wooden car race in Champigny near Paris as early as 1902; however, while there are written records of the first race in the foothills of the Taunus mountain range, none exist for this French race. However, the headlines about the Oberursel race weren’t all positive. The daily newspapers in Oberursel, Der Bürgerfreund and the Lokal-Anzeiger, reported that the car belonging to brothers Eberhard and Josef Steden had been sabotaged. Built by their older brother, Jean, the car was expected to have every chance of success, thanks to “significant improvements to the wheels and steering.” A man secretly tampered with the speedy little car before the race, and during the competition, the steering mechanisms failed – it was a miracle that no one was hurt. An investigation determined that the control cables had been cut; another racer’s father was discovered to be the culprit. Even at this very first race, false pride and criminal intent were on display.

CONCEALED LEAD WEIGHTS, STRICT CONTROLS

Later on, when the prizes offered by the big derbies totaled up to 5,000 marks, other participants fell victim to the temptation to use illegal methods to speed up their cars. They made them heavier with concealed lead weights; inspectors would spot check by drilling into the wood or papier-mâché to see if the racers were trying to gain an undue advantage. The inspections strained the nerves of many participants; the rules were very strict, even in the 1950s, and many racers new to the sport were forced to make last-minute changes before a race or were prohibited from racing at all. The stability of the construction, the reliability of the brakes and steering, and especially the weight were the reasons that often caused racers to be disqualified.

Exact specifications: The kits for junior athletes were delivered with meticulous instructions.

THE SOAP BOX BOOM OF THE 1950s

The golden age of soap box derbies began in the 1950s, when Opel launched an official competition in Germany. The young drivers who competed for the “Opel Grand Prix” had to be between 11 and 15 years old. The automobile manufacturer followed the American model, providing standardized technology and construction manuals and handling the organization of events. Instead of spot tests with drills, inspectors used modern infrared technology to detect illegal materials. Car and driver could not exceed a combined weight of 113 kilograms.

CRASH HELMETS REQUIRED, GIRLS NOT ALLOWED

The rules were strict. The car had to be built by the driver himself. Outside help could only come from other children under 16 years of age. Only the wheels supplied by Opel could be used, crash helmets were required, and girls were explicitly forbidden from participating. “The soap box derby is an event for boys, and organizing the race is a man’s job,” said the rulebook.

SPEEDS OF UP TO 50 KPH

The derby race track was 350 meters long, and the starting ramp was 1.2 meters high; a four-percent gradient allowed the vehicles to reach speeds of 40 to 50 kph shortly before the finish line. Racers were often neck and neck, so after just a few events, the organizers started using photo-finish cameras to determine exactly who crossed the finish line to victory first. Racers also had to adhere to a strict dress code: “Standard and race-day attire includes a white cap, a racing helmet, short black pants, and a yellow racing shirt provided by Opel.”

Mass magnet: In post-war Germany soap box races were an extremely popular sport.

TAKING THE OPEL TEAM BUS TO A NATIONAL EVENT

Participants traveled to the championship derby in Duisburg-Ulmenhorst in Opel team buses. Once there, they moved into their training camp at the home of the West German Soccer Association. The winner of the race would receive 5,000 marks in prize money, a guaranteed trainee position, and a trip to the U.S. to participate in the All-American Soap Box Derby in Akron. During this era in Germany, the derbies became a national event; prominent athletes such as Helmut Rahn and Max Schmeling could be spotted at the races. In 1971, after 23 championships, Opel withdrew from soap box derby racing. Deutsches Seifenkisten Derby e.V. was founded in Frankfurt two years later to serve as a successor organization and has organized the German and European championships ever since.

TODAY, LASERS ARE USED TO CHECK THE ALIGNMENT

A lot has changed since those days. Materials like fiberglass-reinforced plastic have replaced wood and papier-mâché in the chassis, and an axle suspension makes the cars faster. What’s more, racers with a serious desire to win use lasers to check the alignment of their cars. Aerodynamics is likewise becoming increasingly important, with numerous clubs dedicated to soap box derby racing there to provide technical support.

With glass fiber reinforced plastic and an aerodynamic shape: This is how the current senior class soap boxes look like.

A JUNIOR-CLASS CAR COSTS €600

The kits and components for the cars that compete in the races are offered for purchase by Deutsches Seifenkistenderby e.V.; a junior-class car costs around €600. The most important change, however, involves the gender of the racers themselves: Girls are now participating, and increasingly, they rank among the winners. In addition to precision handiwork when building the car, a calm hand on the wheel is also a must during a race, and girls seem to have a talent for steady driving.

The Race Car:

Today, there are two national and three international classes that either apply to different age groups or require different construction specifications. In Germany, there are derby-standard junior and senior cars. The former can be operated by drivers aged 8 to 12. The chassis is designed for a seated driver, and at maximum, it is 205 centimeters long, 45 centimeters wide, and 43.5 centimeters high. Permitted construction materials include non-splintering woods (no particle board), and the axles, wheels, brakes, and steering must be provided by Deutsches Seifenkisten Derby e.V. The car and driver (in racing gear) may not exceed a combined weight of 90 kilograms. A complete building kit costs around €500.

The senior class is intended for drivers between 10 and 16 years of age, and they may drive in a sitting or lying position – however, the latter requires rollover protection. The maximum vehicle length is 2.15 meters, the minimum width is 30 centimeters, and the minimum height is 34 centimeters. Wood and synthetic construction materials are permitted, as long as they are non-splintering. The maximum total weight is 113 kilograms. A mechanical parts kit (wheels, axles, steering, brakes) costs €350; a complete kit costs around €700.

Stock Cars, Super Stock Cars, and “Scottie” Masters Class Cars (with total prices between €600 and €800) are driven in the international derbies.

The Race Track:

The umbrella organization for soap box derby racing in Germany, Deutsches Seifenkistenderby e.V. (DSKD), recommends that organizers provide a race track that is approximately six meters wide and no longer than 350 meters. Four percent is an ideal gradient, and the surface must be smooth asphalt; there should be no protruding manhole covers or other impediments on the track. DSKD can provide support in organizing the race, and individual associations also offer starting ramps, electronic timing systems, and sound systems.

More information and event dates available from:

Deutsches Seifenkisten Derby e.V.

54340 Klüsserath/Mosel, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0) 6507 – 99 1 66

Fax: +49 (0) 6507 – 99 1 67

E-mail: OZ@DSKD.org

Web: www.DSKD.org

The Exhibit:

The Vortaunus Museum in Oberursel documents the history of soap box derbies. Vehicles that competed in races in various years, an original Opel construction kit, individual components, photos, video reports, and newspaper articles all bear witness to the soap box derby tradition in an entertaining way. The museum is opens at 8 a.m. on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, at 10 a.m. on Wednesday and Saturday, and on Sunday at 2 p.m.

Vortaunus Museum

Marktplatz 1

61440

Oberursel/Taunus, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0) 6171-50 22 32