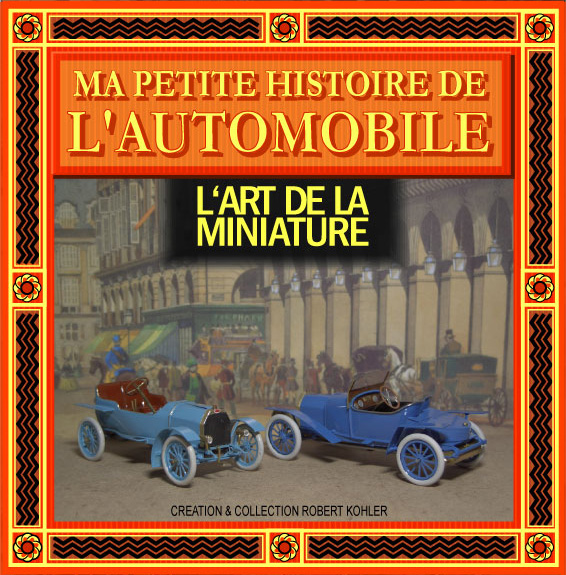

The name of the exhibition, which will remain on display in the Cité de l’Automobile until the end of August, translates to ‘My little history of the automobile.’

Kohler’s collection includes a total of 123 dioramas he has built himself, featuring a total of 650 car models.

“A car is a useful machine. My emotional connection to it doesn’t go beyond that.” Robert Kohler, who was born in 1948, is in the French city of Mulhouse, in the middle of the famous, impressive National Automobile Museum – Schlumpf Collection. He isn’t just a visitor to this site (which, with well over 400 classic cars, is the largest automobile museum in the world); his work is also exhibited here. The name of his special exhibition, which will remain on display in the Cité de l’Automobile until the end of August, translates to ‘My little history of the automobile.’ How can it be that this exhibitor in an automotive museum doesn’t have an emotional connection to cars?

Robert Kohler is an archeologist,

or, better put, a ‘carcheologist’

A closer look at Kohler’s own history explains this seemingly perplexing circumstance. Robert Kohler isn’t a collector of luxurious classic cars or elaborate historical car bodies. The name of his ‘little history of the automobile’ is to be taken literally: He brought it to Mulhouse in the trunk of a station wagon. Kohler, who originally hails from Switzerland, collects and constructs miniature models and places them in dioramas. These are display boxes decorated with historically recreated background images. The car models themselves are only a few centimeters tall. These aren’t fantasy models, though; they are accurate 1:43 reproductions of the real things, even though the ‘real things’ have not been in use for a long time. This kind of work does not require an emotional connection to this past; after all, Egyptologists do not necessarily develop feelings about the artifacts that they excavate, restore, and reconstruct. In a sense, Robert Kohler is also an archeologist, or, better put, a ‘carcheologist.’

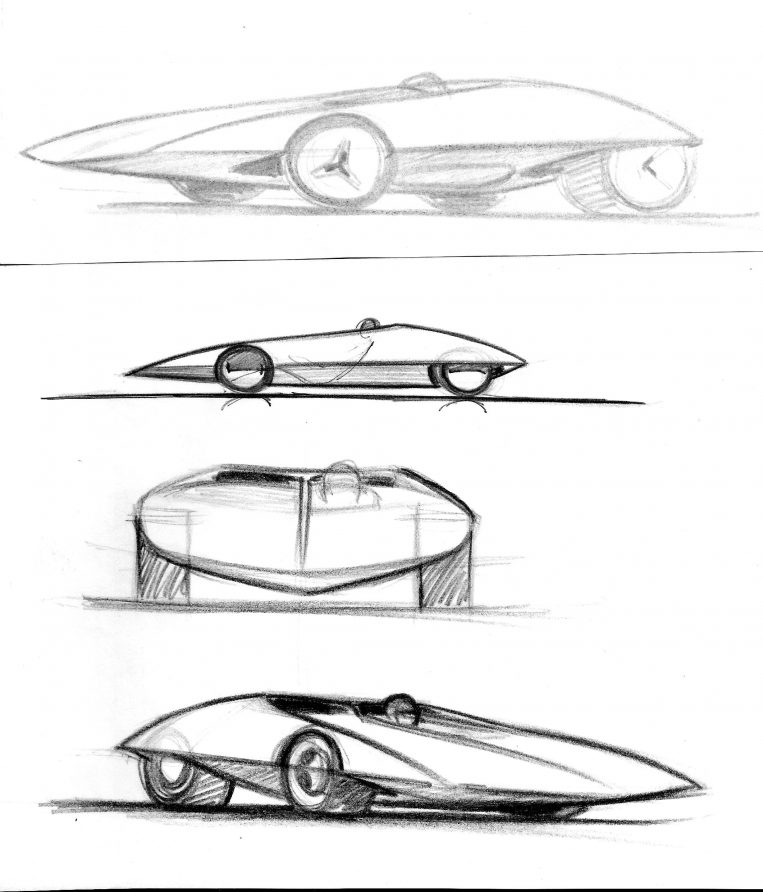

Kohler has long been living in Paris, but he was born and raised in Switzerland. Ever since his early childhood, he has collected car models. “I received my first model as a gift when I was three or four years old,” he recalls. Later on, he secretly built toy cars using his older brother’s tools. His life changed forever when he heard about a competition for young designers that General Motors held in 1965 – Swiss applicants were also welcome. The task was to design a ‘car of the future’ and build a model of it. First prize was a three-week trip to the United States, including a visit to the GM Technical Center and Design department. This proved to be the perfect challenge for this young automotive design fan.

From collector

to designer

Kohler didn’t just build one model: He built three. 400 models were submitted from Switzerland, and Kohler’s entries both made it into the top ten, securing third and eighth place. The next year, Kohler placed fourth, which further fanned the flames of his ambition. He was already certain that he wanted to become a designer – and that he had to win this competition. As a happy coincidence, a Design department was being built at the Opel site in Rüsselsheim under the direction of Erhard Schnell at this same time. Kohler spontaneously decided to apply for a three-week internship there, and the doors opened wide to welcome him.

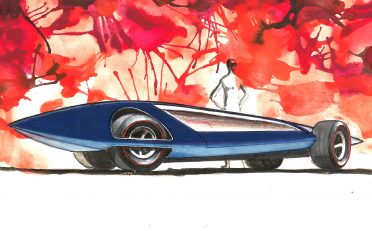

Kohler was already working on designing futuristic cars as a teenager: “When you put an idea onto paper, you prepare small sketches. They have something lively and dynamic about them.”

Timeless fascination: “The advantage of small things is that you can observe them from all different perspectives.” This photo shows Kohler during his internship at the Opel Design Center in Rüsselsheim in 1966.

It wasn’t enough for Kohler to sketch ideas…

… he wanted to turn those ideas into completed models.

Kohler fondly recalls his short but intense time at Opel in the summer of 1966: “When I was there, I started by learning how designers prepare sketches. I was quickly able to work on a new model, design it, and create it using modelling clay. I submitted that clay model when I entered the design competition for a third time.” Once again, he fell just short of his goal: Kohler, who had just turned 18, placed second. A few months later, he received a telegram from Detroit informing him that his model had won a special prize. Nevertheless, it was not quite the result he wanted. The following year, he finally triumphed and won the young designer competition. Despite receiving several job offers from styling studios, he decided to finish out his secondary school and study in Lausanne. Kohler followed his passion and earned a diploma in industrial design. He went to Paris and took along his car models, which continued to grow in number. He founded the product design agency Kohler & Co. in the French capital in 1975.

Interning at Opel: Opening

the doors to a world of design

In 1999, at the age of 50, Robert Kohler closed his design agency. He spent the next few years working more and more intensively with the early era of automotive development. “My oldest models come from the years 1895 to 1897. I don’t have any older ones; I was unable to find any. Obviously, nobody is interested in them besides me. I began researching, collecting books and images – and faithfully reconstructing these old cars as miniature models.”

Kohler’s dioramas are far more than backdrops for miniature models: They are historically accurate windows into the past.

Kohler’s first exhibit, which consisted of three dioramas, was very well received – to his great surprise. The idea to develop a small business out of this exhibit and to cooperate with various automotive manufacturers did not come to fruition. However, Kohler persevered, working, researching, collecting, and continuing to build. And once again, doors opened up for him. He was invited by the Marquis Henri-François de Breteuil to exhibit at the aristocrat’s Chateau de Breteuil, located 40 kilometers southeast of Paris, for five years. Later on, Kohler exhibited at Renault facilities as well as in various museums in Paris and his hometown of Geneva. All the while, he continued to build new dioramas and new models. Today, his collection comprises 123 dioramas with a total of 650 car models, 300 of which are extremely rare or one-of-a-kind pieces. His ‘little history of the automobile’ covers a timespan from 1860 to 1990. Kohler has been exhibiting his work for 11 years – but only small portions of it at a time. Maintaining an organizational overview of it all is a Herculean task in and of itself.

Telling big stories

with little pieces

Kohler can tell a story about the past as well as a personal anecdote related to each and every model – and he is passionate about doing so. Firstly, the models are a part of his life and an expression of his own creativity. Secondly, they not only serve as windows into the history of technology, but also into that of society. As such, the historic car models in his dioramas are parked in front of recreations of the original façade of the first Parisian coffeehouse, for example. Kohler lovingly recreates the details as well as the historical contexts of the respective epochs. The experience and skills he has gathered and honed over the years allow him to create sketches that are true to the original cars using just a single historical image, and to then bring said cars to life on a miniature scale. “I only need up to two days to make a model,” he says.

Thanks to the skills he has developed over the decades, Robert Kohler only needs a few days to construct a model.

A historic Opel “Stadtcoupé 1908” also has a place in Kohler’s collection.

A historical image is enough for Robert Kohler to create a sketch, which he then uses to construct a model that is true to the original.

Design in miniature

An old image does not always immediately reveal how a vehicle functioned. Some puzzles remain unsolved to this day.

But why doesn’t he have any particular emotional connection to cars today? “My love for the models is far greater,” emphasizes Kohler. And models let him live out his passion for design: “I love ideas and concepts, not so much the object itself. When you put an idea onto paper, you prepare small sketches. These have something lively and dynamic about them. If you try drawing them larger and in greater detail, something gets lost along the way. Small-scale designs have the advantage of being condensed: The human eye can capture a small sketch in its entirety at a glance, and the same applies for a small model. And you can observe small things from all kinds of different perspectives.” A look at his dioramas proves that small things can be truly beautiful.

Kohler is not merely

interested in constructing models

Kohler’s love for automotive design primarily applies to its early years, which he associates with names such as Daimler as well as De Dion-Bouton and Panhard. His interests span through to models that were developed after the mid-1990s. Kohler finds the variety among earlier development approaches fascinating. “Some automotive pioneers focused on different and competing types of engines, while others focused on designing their own vehicles and bought the engines for them from other sources. Different manufacturers focused on speed, new types of drives, and lightweight constructions. They also dealt with all kinds of different conditions, including regional ones, which strongly influenced automotive development. For example, for some time, the English were lagging behind the Scottish in terms of vehicle construction. Why was that the case? Because in England, there was a law that stipulated that motorized vehicles could not be driven alone. Someone always had to run ahead to warn others on the road. That put a halt to English development for a long time.”

Kohler is not merely interested in constructing models. His true passion lies in bringing history to life; that’s what differentiates a model-builder and collector from a true ‘carcheologist.’

The story behind the Schlumpf Collection

The Schlumpf brothers

The Cité de l’Automobile in Mulhouse is considered the largest automobile museum in the world.

The brothers Hans and Fritz Schlumpf (1904–1989 and 1906–1992, respectively) numbered among the most influential patriarchs in the French textiles industry in the late 1950s. Their four spinning mills dominated the market for combed yarns. When the Bugatti factory in Molsheim closed down at the end of the 1950s, Fritz Schlumpf decided to do his part to preserve the storied manufacturer’s legacy, collecting a total of 87 vehicles made by the Bugatti brand.

It was not long before his passion for collecting branched out beyond Bugattis. Between 1961 and 1963, Fritz Schlumpf purchased around 200 European automobiles – mostly through frontmen – and secretly placed them in storage. In 1965, he began nursing the idea of opening a museum, and started converting the former production hall of the textiles factory in Mulhouse into a 17,000-square-meter exhibition hall. Over the next ten years, he invested around 12 million francs into his passion. However, the museum never opened, since the money came entirely from the company assets.

In pursuing this dream, Fritz Schlumpf drove the entire textiles empire into ruin in 1976. Nearly 2,000 employees lost their jobs. During the bankruptcy proceedings, the Schlumpf brothers fled to Basel. The photos secretly taken in 1977 by Jürg-Peter Lienhard in the Schlumpfs’ private museum confirm all of the rumors circulating about the self-indulgence with which the brothers diverted operating capital towards their private collection. After these images were published, the majority of the workers staged a sit-in at the collection, claiming it was “collateral against their lost jobs.”

At the time of the occupation, the ‘luxury playroom’ of the Schlumpf brothers included 413 restored classic cars as well as dozens of unrestored models, numerous motorcycles and bicycles, half a ship, and a dual-engine Douglas DC 3. The brothers could have paid off the claims made against them by creditors by selling off the vehicles. However, the French government intervened to ensure that the collection was preserved in its entirety. In 1982, the Musée nationale de l’Automobile opened its doors. It has been known as the National Automobile Museum – Schlumpf Collection since 1989.

Hans and Fritz Schlumpf were charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and embezzlement of company assets. This affair attracted international notoriety and sparked a years-long legal proceeding. This stubbornly continued years after Hans Schlumpf’s death in 1989 – and did not come to a conclusion until shortly before the death of Fritz Schlumpf three years later. Due to his advanced age and his dementia, Fritz’s four-year sentence was reduced to a one-year suspended sentence.

In March 2000, following extensive renovations, the largest automobile museum in the world was reopened. Following an expansion, ‘Cité de l’Automobile’ was added to the museum’s name in 2006. In 2011, the ‘Autodrome,’ an exhibition track that can seat 4,500 people in its stands, was inaugurated. Historic vehicles have been brought back to life there ever since.

↑ Insights into the collection

May 2017